The bizarre experience of going across the world to find out strange things about strange places. My experiences of fieldwork, and life in the Dominican Republic

Sunday, December 24, 2006

- A quick note to anyone who might be travelling in rural Dominican public transport, especially during busy periods. Bring plenty of caribiners so you can clip yourself and your luggage to the side of a pickup truck. Particularly important if your driver likes to take hairpin bends at speed, as I have seen luggage, although not people, thrown off the side.

I am glad that I finally caved in to advice and came down early. The roads were heaving with traffic, and every guagua had luggage on the roof, and people hanging out of the doors. My own journey took a bit longer than usual, not just because of the traffic, but because we got a puncture and also the engine exploded in the middle of the motorway. Our handy chofer fixed the thing in 5 minutes, Dominican style, with bits of electrical tape and an old t-shirt. A bit like Blue Peter on acid. However, the traffic wasn't too bad heading into the city, as most Dominicans go to stay with their family in the campo for christmas. Outbound traffic was horrendous, with big queues for guaguas.

I am a bit miffed at missing the party though, as I was assured of a good time. They were going to do a giant sancocho, a traditional stew, enough for the whole village. This was to be followed by the annual angelito, where villagers exchange gifts, having picked a name out of a hat a few weeks back to decide the victim of their secret present. Lots of individual households were also going to roast a pig over a fire - on Saturday morning at 7AM I was rudely awaken by the deafening squeals as my neighbours slaughtered their swine. They then gutted it and shoved a big pole through it to hang over the flames. There was a surreal sight of several pigs-on-a-stick lined up outside the corner shop. The rest of the night was to be taken up with dancing, and several ladies had promised to show me how to strut my stuff, Dominican country style. Tragically, I am going to miss this, but it's my birthday in a few weeks, so perhaps I will get a dance then.

Whilst in Santo Domingo, I am going to have an orphans' christmas with all the other foreigners I know who don't have enough money to fly home and see their family for christmas. Feliz navidad

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Of course, in all walks of life, one has to accept that not all people have the same opinion as you, and that you must respect that. However, there are somethings that are harder to cope with than others. In particular, I do get shocked by the way children in my village get treated.

Of course, children here are certainly well loved, and the intention is most definately there to take care of them. If their parents are out working in the fields, the children are passed around neighbours and relatives in a way that perhaps a lawnmower or a really good novel is passed around in UK society. Like lawnmowers and novels, they are given a lot of attention, then returned with a slight smudge from an unrecognisable source.

Perhasp it is because my own mother has spent so many years working in public health, but I do struggle to restrain my moralising tongue when I see what they feed their babies. Most women in the village have their first child age 15, disturbingly often with their cousin. It seems that breastfeeding is virtually non-existant, instead mothers go out of their way to feed them with powdered baby formula. I don't know if this is because like many other things in the DR people automatically assume that a shop-bought 'American' product is better than the indigenous or natural product, or if it is for far more controversial reasons. Like almost all other universities in the UK, my employer has banned all Nestle products from its union shops, on the basis that Nestle is aggresively marketing powdered baby formula over breast milk, the natural option being better in 99% of cases, with the risk in formula of illness from dirty water, and therefore putting company profit over babies lives. The water in the village is exceptionally clean, though not flawless, particularly for young babies with weak immune systems, so the issue becomes the relative expense and the absense of nutrition and natural antibodies when missing the natural product. This boycott of Nestle is a central tennet of the right-on thinking that dominates student politics, but it is also a view that I have some sympathy with, given my own experience.

Out here in the campo, all of the colmados (village shops) have some brand names painted on the outside wall, so the casual passerby can clearly see what this shop sells. Common brand names include Presidente beer, Verizon phonecards, and Nido, a Nestle baby formula. I don't

know if Nestle have paid for these signs to be put up, or whether this constitutes an aggressive marketing campaign that turns mothers off breast feeding, but it is certainly grounds for suspicion. For once, I think I support the right-on thinking of the wannabe parliamentarians in Student Unions across the land.

It would be far more challenging for these people to incorporate some of my other observations into their thinking, as some of the other stuff people here feed babies cannot be blamed on ruthless international capitalism. Seeing a three month old baby given sweet coffee and sugary soft drinks, and a four year old given neat rum to drink shocks me. I can bite my tongue many of the other things that go on here, the views on Haitians and so on, but I really struggle from criticising my friends when they feed such stuff to their babies. I can try and formulate academic reasons for it, such as a developmentalist discourse that automatically assumes that 'modern' products are better than 'traditional' or 'natural', but it is no use. So far, I have managed not to burst into a lecture, though I did in another village when I heard the shockingly ignorant views of a local teenager on the causes of AIDS, and how to prevent it. I felt it was my moral duty.

Talking of babies, congratulations to C and S on the arrival of M!!

Warning: This blog contains infantile humour and references to animal cruelty.

After weeks of failures, when I arrived late on the scene to find only blood and feathers, I finally saw my first cockfight, an important part of rural Dominican life.

I wanted to see a cockfight partly because of the brilliant essay on Balinese cockfighting by Clifford Geertz (anthropology great of the 60s/70s), where he finally got accepted into his village after months of trying when he got busted by the police attending an illegal cockfight, but mainly I was driven by curiosity. I didn’t really need to attend a cockfight to become accepted in the village, as my fast spreading reputation regarding my inability to dance even whilst sober sorted that out - people are telling me all sorts of wonderful secrets after only a week of knowing me.

The first fight I saw was one on a little side path off the village road, rather than one at the cockfighting arena (i.e. shack) down the road. Such fights are used either to train novice cocks so they are ready to fight on the main stage, or to fight the weaker chickens who can’t handle the fiercer competition at the arena. Despite this being the second division of cockfighting, the handful of observers still got pretty excited by the whole thing.

It starts with two people with their cocks in hand, stroking them and eying up each others’ for size. They then set them on the ground and let them loose for a few seconds only, to see that both are in the mood for fighting and won’t run away. Regulation spurs are fitted, a designated timekeeper is set, and the chickens are let loose. I am not sure I understand the exact rules, but it is not just a simple matter of two chickens pecking and scratching each other to death. At the arena, where fights are every Sunday afternoon, the rules are stricter and written into Dominican law – there are even weight categories like in boxing, though there are perhaps more featherweight and Bantamweight categories in cockfighting.

The fight was a lot less spectacular than I expected. Cocks stare at each other for a few seconds before a flurry of wings as they peck at each other’s heads, slash each other with the spurs, or pin the other down with their wing to make pecking or slashing easier. The occasional feather or drop of blood splashes around, and after twelve minutes, a winner was declared. The proud victor was cleaned and petted by its owner, whilst the loser was dispatched for soup. Apparently it makes a particularly rich soup, the adrenaline released in the fight giving a distinct flavour to the meat.

Cockfighting is a crucial part of Dominican rural life, and an area that I am yet to scratch the surface of. The champion cock breeder in the village is an eighty two year old man, who is rarely seen without a cock in hand, and who mumbling to me how cockfighting is a reminder of life, struggle and death that is important to him in his old age. Certainly the cockfighting culture is much more than a simple exercise in sadism that it might be portrayed as. A good cock is described as being “brave” rather than strong, and there is great admiration for the many cocks who refuse to give up and fight vigorously to the very last.

After living a year in

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

When I have been making enquiries about relationships here, everyone keeps telling me "we are all family here", and they are certainly not lying. The easiest way I can put it is that it is a 'limited' gene pool. Everyone seems to marry their cousins and the family trees are soon resembling plates of spagetti, with links in places which are as surprising as their are worrying. Unfortunately, one does not have to look closely to see that this lack of genetic diversity has had some clear effects on some individuals.

Despite my community being a stereotypical mountain village, I am rapidly becoming more certain that I prefer being with these people than with your average Santo Domingo resident. I can never do an interview or even walk past a house without being invited in for a cup of coffee and a blether, and often I get given a plate of rice and beans during any interviews I do at middday, without even being asked if I am hungry. It takes me so long to do the tasks that I set out for myself each day, simply because I get distracted by another unplanned conversation. I rarely complain because these almost always give me some more information on life in the village, revealing a previously hidden aspect to life in this close community.

The village is strung out along the road, with my shack being at the extreme of one end (technically in the next village, but they forgive me for that), and the other end of the road is 3km away. Despite this being a relatively short distance, I find myself using my motorbike to go to meetings at the other end of the village, simply because I know from experience that if I go by foot I will probably not make it, as I will be distracted and delayed by another cup of distressingly sweet coffee.

I did go to the Shakira concert last night, which was an excellent show, but my blood pressure is too high to tell you about it, following the disgustingly inconsiderate behaviour by spoilt middle class Santo Domingo brats. As my friend commented "it was a great concert, but it was a shame it was in a stadium full of the rudest people on the planet". The best moment was when Shakira informed the stadium how much she loved being in Santo Domingo, just as divine comedy intervention chose that moment for the power to go out - "ah, we have a problemita", she commented. How true, how true.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

For example, the American embassy is a big sprawling complex covering several blocks of middle class Gascue barrio. The embassy, the consulate and the international aid buildings are all surrounded by three metre high concrete anti-car bomb walls, policed by severe looking chaps with big guns. They recently staged a three hour unannounced "anti-terrorism" excercise, waking up middle class slumberers at 6 AM on a saturday with armed troops running around, blocked streets, smoke bombs and the like. I know there is an anti-yanquista movement here, but they are a bunch of students who couldn't possibly pose a security threat.

I recently interviewed a senior official at the international aid branch of the embassy. It literally took me half an hour to get through security, they confiscated my passport, my laptop (after taking down the 27 digit serial number, for some reason), my mobile phone, and misteriously my pencil case, which James Bond style actually doubled as a high explosive anti-tank device. So just as well the bored security man took that off me. I had to pass through the metal detector twice (once would normally been enough, but theyhad forgotten to switch it on, so I had to do it again). I then passed through into the embassy to meet my interviewee, who then informed me that it was a bit stuffy inside and he would prefer it if we went across the road and sat in the park to have our chat. I gave the security man a dirty look as we walked past into the park, with its tweeting birds and members of the Caribbean branch of al-Qaeda behind every tree. Last week I ran into members of his family in the mountains where they were having a weekend camping. Makes a mockery of the situation.

The French embassy, like the Italian, Mexican, and Trinidad and Tobaggon representations, is house in a grand colonial mansion. It is an elegant, refined edifice that once was owned by Hernan Cortes before he went conquering Mexico and looking for El Dorado. It may also have been the house of Ponce de Leon, before he off to Florida to find the fountain of youth - it was unsuccesful as he died of typhoid in the first few months of his trip. Whatever he drank, it wasn't the fountain of youth. I think the French embassy has been there ever since, and it exudes a gallic air of snobbery.

The British embassy, for some unkown reason, is in the seventh floor of a decrepit insurance company in a depressing shopping district. It is truly a half-arsed attempt. There is no sign at street level to inform you outside the representation of Her Britannic Majesty's Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and you have to take the lift as the stairs have fallen down. Once you get into the building, security is minimal - the job of the security guard is merely to politely request, if you don't mind, to do something that goes against every part of the Dominican psyche, and turn off your mobile phone and wait your turn in the queue. How marvelously British.

I forgave their choice of location after that, and was only slightly disappointed not to be offered tea and crumpets.

Monday, December 18, 2006

In case I haven't told you, I have christened my bike in tribute to Che Guevara's bike in The Motorcycle Diaries: His was called El Poderoso (the mighty one), and mine is now known as La Flaquita (the weakling). She has certainly been struggling to get up the main road that travels into the mountains where I live, which is four thousand vertical feet of hairpins and potholes.

It is a veritable lesson in tropical biogeography that would delight old Professor Furley. At the start, as you climb out of the rice and tobacco growing plain of the Cibao, the roadside trees are dominated by cocoa small holdings, with red and yellow cocoa bean pods hanging from the branches. Further up and the smallholdings get too cold for cocoa, and turn to coffee, grown in the shade of many trees that I know neither the spanish or english names for. The slopes are very steep and very green, different shades but always at about 50 degrees to the horizontal. As you rise, you do so along with the air brought in from the Atlantic, which cools as it rises, leaving an almost permanent blanket of cloud at around 3000 feet. This is too cold and wet for coffee and other cultivars, so are dominated by Magnolia, with epiphytes growing up on the branches. This is prime territory for orchids, and there are some species that are only found on this particular slope. Further up and the air gets truly soggy, so that the top of the pass is populated by tree ferns. I notice the vegetation more on the way up, as I crawl up at walking pace, the engine squealing away. On the way down, I am too busy looking at hairpins and potholes to notice the trees. Just at the very apex is a shrine to la Virgen, and people either stop to light a candle or cross themselves as they pass it. This is either to give thanks to their engine for putting up with climb or to ask for divine protection before diving down the descent.

I live just in the lee of this pass, so while not quite as cold and wet, I am still woken up in the mornings by the sound of rain on my corrigated iron roof, to see my breath in the air. It takes a few cups of coffee before I remind myself that I am in the Caribbean.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Women here seem averse to wearing anything that doesn't have at least a three inch heel. Indeed they prefer it to be five inches, and platform. The shoes must not be simple brown or black, but must be a bright colour - flourescent green appears to be 'in' this season. A Santo Domingo lady chooses her clothing by starting at the feet, and working up, making sure everything is matching. Even Joan Collins couldn't out-powerdress these girls. The heels should be as loud as possible, so that not only do you tower out from the crowd on six inch height extending stilletos, but everyone will hear you coming as you clack-clack-clack along.

I hear that the fashion for flatform and high heels dates back to Rennaiscence Venice, where what was a practical measure to avoid getting wet feet on the flooded cobbles of St Marks became a way to get one over the rest of the society girls. The competition to have the highest platform shoes grew to such a height that they topped thirty eight inches, and having such an extended centre of gravity, the women had to walk with a servant on either side to support them as they waddled along. It was all worth it, as not only did you show that you were rich enough to buy ridiculous high heels and to have two servants to help you, but it showed that you were so separated from having to earn a living through work that you could strap on such ridiculous footwear as you pop out to buy a pint of milk and the paper. Santo Domingo women always make sure they are wearing innappropriate footwear when pushing the supermarket trolley.

You must bear in mind that Santo Domingo's streets are irregular, full of potholes, broken pavements, dogs, street vendors and other inconveniences. I struggle to walk aroun in my oh-so-sensible trainers, yet these ladies seem to manage fine. They get in and out of public transport wearing them, althought they do it subtly so that people don't notice that they are dismounting a guagua rather than a yipeta. It appears that the only thing worse for ones social standing than not being in ridiculous footwear is to fall over in heels. It has made me wonder if there is a kind of Darwinian process at play, whereby through natural selection Dominican women have developed a type of femur that can only function if supported by a towering heel, rather than flats. I have extended this idea, and decided that Dominican women who fall over in heels are treated like racehorses who fall and break their legs - they are shot and boiled down for glue.

Dominican men are no means less fascinating. All men, no matter what their position, must have immaculate black shoes. Even the people who I know struggle to pay the bills will always leave the house in polished black shoes. The shoes may be full of holes, the sole worn out, but they will be so polished that you can see your reflection. This is all the more surprising when you consider how dusty Santo Domingo streets are when the weather is dry, and how muddy they are when it rains. Providing a mobile service in maintaining one's mirrorlike lustre to one's shoes is the small army of shoe shine boys. These guys run around the city with an empty 5 litre oil can and a small box contain the tools of the trade. For a few pesos they will sit on the oil can with your foot up on the box, and restore the glossy finish with professionalism and care. Budding little capitalists.

I get away with my practical, dependable, dust coloured trainers because I am a gringo, and therefore am not expected to dress decently. God forbid that I would wear flipflops though.

Just to put you in the picture, I have spent five weeks working in a huge, bustly, polluted, noisy, 24 hour, sociable city, living in a great apartment with somebody (an American) who I can relate to when I need to be less Dominican, but who knows such a huge amount about the culture here that they have a source of many a great pointer. I have also had wireless internet access, permanent mobile phone coverage, reasonable electricity supply and a water supply that only works half the time, but at least I know which half it will or won't work. I will move from this to a tiny shack in a small mountain village with a few hours a day of unpredictable electricity, no running water, a half hour journey to pick up mobile phone coverage and important text messages, no water and a bunch of campesinos who I am sure will be welcoming and friendly, but who occupy a different world from myself. In a strange way, I feel that Santo Domingo is far closer to my world in the UK than it is to the mountains, even though the geographical distance is 100 miles rather than 8,000.

However, I know that I have lots of work to do up there, and that will keep me too busy to feel isolated, and that I need to be back in Santo Domingo on the 19th for the most important meeting of this trip:

I am going to a concert featuring Columbia's second most intoxicating export, Shakira. And I can't wait.

Monday, December 04, 2006

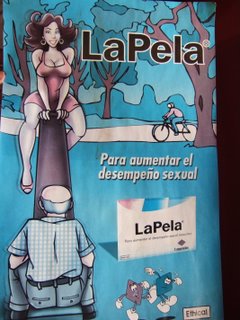

Here is an interesting poster that you see all over the place. I am sure I don't need to explain what this little pill supposedly does. The ubiquity of it is what surprises me, and they sponsor one of the major baseball teams - all those muscly sportsmen with the name of a "male help" pill on their backs.

I am a bit confused over this in a number of ways. Firstly the pill is called "La Pela", and my understanding of the word pela is that it is a slang term for a beating - "I am going to give you a 'pela'" means I am going to thump you. Quite why this is has become a name for a small blue pill is beyond me, though I am sure some feminist discourse analyst could spend many a happy year analysing it.

The link with baseball is also amuses me. There is a rival brand that makes a great deal about how it is endorsed by none other than David "Big Pappi" Ortiz, a major league batsman. Unfortunately, the nickname is not my invention, but on the poster is actually in a larger font than his first or last name. Their publicity has an interesting picture of "Big Pappi"; a huge, grinning, muscly baseballer gripping a baseball bat in a way that clearly shows he is compensating for something. I don't think the concept of male compensation is present in Dominican culture if all the blue pill manufacturers endorse big muscly sportsmen who swing bats. Either that or they have highly developed sense of irony, which I doubt.

Apparently these endorsements are worthwhile, as these pills are incrediably popular. You have young men popping these pills like crazy (surely young men are the people in least need of such artificial stimulants, or maybe I should ask their girlfriends. Though this sort of person probably doesn't have one). It has become a bit of a health risk as it is tampering with blood pressure.

The most surprising bit is that people here will openly talk about how they use them. The DR is an incrediably macho society, and no bloke ever wants to show their weakness here, least of all in the trouser department, yet that is not how it seen here. Rather it is seen as a point of pride that you have so many girlfriends that you need help in keeping them happy. Though I don't see why you couldn't just try helping them go shoe shopping......

Anyway, I think the DR is a long way from metrosexuality. I'll put my plans for a male moisturiser import business on hold.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

For example, meeting Dominican civil servants (who are never particularly civil) are people who work very much on la hora Dominicana (Dominican time). I arranged a meeting with someone at the environment ministry, scheduled it for 10 AM. I arrived at 9:55, all prepared and ready, only for the interviewee to turn up at 11:45, without so much as an apology for being late. I soon became used to Dominican time, and incorporated it into my working day. It is perfectly reasonable here to schedule a meeting a full hour before when you want it, knowing that people will generally turn up around an hour late. Most Dominicans appear to live in a time zone about 1 hour behind GMT (Gringo Mean Time). I have a suspicion that the same social trend observed in the lecture I went to applies here - that the later you turn up, and the more disdain that you give to people who expect you to turn up on time or at least apologise for being late, the greater the sense of superiority and importance that you exude. Perhaps a bunch of anthropologists would get excited by the social power things, and would start talking about Bordieau and such like, but anthropologists are a funny breed, and have a unpleasant tendancy to do things like that.

The problem with this is that I have a lot of meetings with foreigners and with Dominicans working at foriegn NGOs and aid agencies. In the DR, if you want someone to turn up within about half an hour of the scheduled time, you say a la hora Americana - American time. My own practice when meeting Dominicans who work for foreign organisations is to think that they have become half-gringoed, and so I expect them to turn up 40 minutes late. With foreigners who live here, I make a calculation on how long they have lived here, and how aplatanado they have become. For someone new to the country, I expect them on time, but for someone who has lived here for ten years, I expect them to be half an hour late.

Yesterday, I suddenly had to think in European time. I had a 10AM meeting with a German aid agency. I made sure I turned up at 9:55, and lo and behold, my German interviewee walked through the meeting room door at 9:59:59. He may have lived here for years, but there is something in the German psyche that prevents them from being aplatanado with regards to time keeping, no matter how long they may have lived here. I wonder how frustrated he must be with Dominican time keeping.

To my dilemna: I have scheduled a meeting for 9AM on sunday morning with an academic. I know that the interviewee is a foreigner, but has lived here for long enough to become semi-aplatanado. She is an academic (a geographer!!!!), and works for the state university here. Therefore my calculation as to what time I should actually turn up at is thus:

9AM sunday morning

-add 30 mins for being a sunday morning

-take away 10 mins for being a foreigner (she is French)

-add 30 mins for being semi-aplatanado

-add 15 mins for being an academic

-add 30 mins for being a state employee

I therefore calculate that I should turn up at 10:35. Sounds perfectly reasonable. I will let you know later how accurate this was, or whether she answered the door in her dressing gown.

I think I should create a website that does calculations like this, to work out the exact delay between the time-keeping of different Dominicans and Gringo Mean Time.

Friday, December 01, 2006

What 'aplatanado' means

Looking at the license documents and ownership papers, there are few interesting sub-clauses, here reproduced;

- All journeys that are longer than 20 yards must be taken on a motorcycle. If you own a motorcycle, it is undignified to use your feet for anything other than the gear shift and the brake.

- Your horn must be used on the following occasions; approaching a junction, overtaking, undertaking, when there are children/chickens/any other detritus in the road, when passing a vaguely attractive female, when people are trying to get to sleep, all other times. The horn is more important for your safety and wellbeing than your brakes - it is used more and should be serviced more regularly.

-In the interests of public wellbeing, your engine should be tuned so that it is as loud and high pitched as possible. Please visit a mechanic if it is not harming the navigation abilities of all bats in a 20 mile radius.

-If possible, avoid making any journeys alone that can't be made with your wife, three children, a propane tank, two chickens, a live goat and a sack of rice on the back.

-When not making journeys, you and your motorcycle should be parked outside the colmado, revving your engine and showing the world you are a man with a bike.

I notice that I have offended people (Chirimoya and friends) with my comments about Dominican cooking and cuisine. I stand by my comments, and invite them to prove me wrong, by having me round and cooking me a great dinner. Over to you.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

The difference between these other places and the Dominican Republic is that they have developed a indentifiable cuisine that can be identified with those places, and they have developed a distinct food culture. It is quite astonishing that the Dominican Republic, with its productive seas, tropical lowlands and cool mountains, and its history of mixing Spanish and French colonial legacies with West African slave histories and a smattering of indigenous influences, has spectacularly failed to develop a national cuisine that you would want to eat.

Much is made in places like France, Spain and Italy about how many of the classic great dishes, like Paella, Pizza, and Cassoulet are essential poor peoples dishes. They take cheap, locally available ingredients and add some innovation and pride to produce something magical. The array of cheap, locally ingredients here is amazing. I was passing through the market today, and alongside the onions, potatoes and apples from the mountain valleys were passion fruit, papaya, limes, plantain, and lots of other things that I don't know the english word for. I even had my first taste of raw cocoa bean straight out of the pod - a waxy texture, the flavour was dry, very bitter, but intense, fruity and definately chocolately.

The bit crucial ingredient missing from Dominican cuisine is care and enthusiasm. Despite the abundance of potential flavours, or because they have been spoiled by it, Dominicans seem to just view food as calories, rather than something to be enjoyed. All the many comedors I have been eating in seem to produce the same food - rice, beans, and chicken (fried or boiled), sometimes accompanied by the flavour-vacuum that is plantain. There is no attempt to be different, innovate, become known for producing a dish that is different or better than all the other comedors in the area. It is often quite greasy, which is OK because it lowers the potential for food poisoning - any bacteria that survived being immersed in hot oil will be killed by cholestorol poisoning. There is no sensitivity or delicacy, everything is boiled or fried until it has given up any potential for flavour or nutrition. Up market establishments are rarely better, they just have air conditioning rather than clackety fans, but the food is equally bland. It is frighteningly depressing, if it wasn't for stimulation from the roadside fruit sellers my tastebuds would have killed themselves long ago out of boredom. I find it amazing that countries such as France can breed thousands of types of types of beans, with unique flavours and textures, yet the Dominicans cannot be bothered to go past two - they probably think that it is already excessive.

This is in the city, I will soon move and live up in the mountains, where there is no tropical fruit, and I will be away from the valleys that grow temperate fruit. Where I will be going they grow coffee and some spices such as nutmeg and cinammon, but because the roads are bad, they can only import dried, non-perishable goods such as rice and beans - no tropical fruit! That is ok, I here you say, as you will be surrounded by spice production and some of the world's finest coffee, but unfortutely Dominicans ruin good coffee by saturating it with sugar until it is so sweet your teeth go numb, whilst the spices seem never to make the journey from the tree into the cooking pot. Rice and beans it is for me.

This has been by far the second most depressing thing about field work (la novia ausenta being number one) and it is driving me mad. If only the Dominicans could take some sort of pride in their food, think about how to cook and make the most of what they have, sensitively coax and cajole flavour into their dishes, not crudely bash it out. If only they could change their food culture towards one that produces a cuisine, like India, Vietnam, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Mexico, it will be a far nicer place to live. So far all it has made me do is vow to go somewhere else for fieldwork next time.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

It soon became rapidly clear that people had turned up not because they were interested in hearing the thoughts of a leading intellectual, but because to maintain their position in the political class they had to be seen to be in attendance. First off, entering the auditorium I noticed that I was virtually the only person not wearing a suit, which means that there were very few academics in attendance, as we would never dream of dignifying a visiting acadmic by making the effort to wear a suit and tie. It would give them too great a sense of self-importance, not good in our egotistic game. Having said that, perhaps it is different here, as Dominicans put an extraordinary effort into presentation - I am convinced that one of their biggest imports is shoe polish. How they maintain a mirror-like surface on black leather whilst living in a dirty, dusty, muddy city is beyound me. I noticed the relation between one's position in multi-stratered Dominican aristocracy and where one parks one's 4*4 (or yipeta as they are known), but this is a topic akin to heraldic shields, and will be explored at a later point.

Anyway, I tried to take my seat, I was asked by a steward which institution I was affiliated. I rose up, puffed out my chest at a the chance to show I was an international intellectual and informed her that I was from the University of Manchester, England, dontchaknow? I was was promptly informed that I could not sit in the front five (half empty) rows, and must sit towards the back of the auditorium. Imagine a lecture in the UK having reserved seating, the outrage there would be. Mind you, the situation would be the reverse, as everyone sits at the back so that they could get a quick exit before the Q and A. Here it is different, it is a clear mark of social status, the proximity to the front. Mere academics are not rated as wanted guests at a lecture by a Professor of Sociology, and must sit several rows behind the government officials, leading businessmen and bizarrely a four star general resplendant in ceremonial uniform. They had to be seen to be in attendance.

Of course, they wouldn't do something as humble as listening to the speaker, they had important things to do, mainly making sure that people notice them. Within seconds of Manuel Castells starting, the first mobile phone sounded. Normally in the UK this prompt a cutting remark from the chairperson, or at the very least a double-checking of pockets and handbags to ensure that you wouldn't be the next victim of a barrage of dissaproving tutting. Here, inaction was the policy and therefore the talk was punctuated every thirty seconds by another CrazyFrog. If they were not letting the phones ring, or even worse, answering them, the audience members took the opportunity to chat the people sat around them. Not a subtle whisper to the person sat adjacent, but a full conversation with your friend three rows back.

The anthropology in this is simple. The social credit gained from people looking at you whilst you talk on the latest mobile phone or chat to somebody, is far greater than any potential social credit lost through interrupting one of the world's leading intellectuals. In fact, the more distinguished the speaker is, the more likely it is that they are interrupted by some trivial phone conversation, as what better way of asserting that you are more important than someone than by interrupting their lecture. The more trivial the interruption, and the more eminent the speaker, the more social status gained. Phone etiquette, such as the totalitarian response that I employ in my classes (if one of my students' phone rings, I answer it, normally with an obscenity), is a completely alien culture here.

The actual lecture that was the distant backdrop to this battle for social supremacy was extremely good. Castells based his lecture on Latin America as a whole, claiming ignorance of the details of the Dominican development experience, and as result I don't know if he appreciates how much he insulted the way of thinking of those present. Firstly he described as outrageous the fact that the DR has had the fastest growing economy in Latin America as well as the fastest growing inequality, and he did so to an audience that had arrived in brand new yipetas, were clearly the ruling elite of the country, and had no intention of addressing the fact that they were the root cause of inequality. Secondly, he stated that the information economy came from lots of failed venture capital in micro-companies that were financed by a few successful startups, to an audience of people who maintain their economic power by stamping on the fingers below (like any academic, I will substantiate this with references, but at a later date). And thirdly, he stated that development in the information age comes from state investment in the things that facilitate increase productivity, rather than grandiose development schemes. This in a country that has cut the education budget to finance a fantastically expensive and probably unworkable Metro system. But of course, a Metro system will always win over investments in education, because it leaves a presidential legacy of Development, Modernity, Progress, Civilisation and turning the DR into a carbon copy of New York.

Of course, the fascinating bit came at the questions. The chair explicitly banned people from making long protacted points about their own perspective in the guise of a question. Imagine trying to do that at an academic conference - there would be lynching! However, although I didn't miss the egotripping, the questions betrayed a lamentable Dominican trait, which is a lack of critical thinking. The questions were simple, boring and largely irrelevant, not challenging any of the ideas discussed, or asking certain points to be expanded upon. I would have lobbed an incisive googly, but sitting in row six I wasn't allowed. An academic here described to me how there isn't the culture in the DR that there is in the rest of Latin America of critical intellectuals, for the simple reason that Dominicans can't take criticism. Here people get offended and will never speak to you again if you even attempt to constructively criticise them, and will kill your pets in return for a mild reproach. Social standing is everything, and woe betide he who is seen to be undermining it. The only way you can make progress is to say "well, you know, perhaps if I was in your shoes, but of course you know best, but perhaps I would consider...."

If people are not prepared to ask the questions, is it little wonder that this country has not provided any answers.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

There is only one person in the country with a PhD in Geography.

Simple.

And he got it from a Spanish university. The president should stop pouring money into the hole in the ground that is the Santo Domingo metro system and invest in postgraduate geographers. I know of at least two Dominicans with Anthopology PhDs, so this begs the question of how a country is to move forward where not only there are virtually no geographers, but also where they are outnumbered by anthropologists. And that is before I even get started on the number of economists.

Mr President, if you are wondering why the country has all of its problems, despite the intense analysis by economists, then it is precisely because you are asking economists and not geographers. If the answer is not 'geography' then you are asking the wrong question. You should do a regression analysis with extreme prejudice on the economists (i.e. throw them to the crocodiles, just as one of your predecessors did with his political opponents), and replace them with geographers. Soon life will be better, everything will work, and little children will run in the sunshine skipping and singing about space and place.

Rant over.

At least this explains why I get looked at funny when I tell people I am a geographer

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

The last few weeks I have been doing lots of interviews in government offices, which seem to be in the stranges places - to get to the national parks service office you have to get the guagua to a suburb that consists of a mix of crumbling apartments, informal housing (slum) and large factories, walk up a sidestreet, up a path past some dead dogs, and through a hole in the wall. It took me ages to find it. Some ministries are big imposing buildings, set back from the road through large archways, but others are up random alleyways in middle class suburbs. I have been buzzing all over the city, and am getting good at asking for directions (and another thing, Dominican house numbers are completely illogical - I was going to number 25, which turned out to be 300 metres up the street from number 27, right next to 141 and opposite number 8. Confusing and very frustrating).

Anyway, the problem is that about 160 years ago, during a time when the Haitians occupied the Dominican Republic, on the 27 of February, the trinitaria of Duarte, Mella and Sanchez, with the help of rich landowners and the catholic church, mounted a revolution, won independencia and kicked out the Haitians. As Dominican national identity is in a vast part determined as not being Haitian, they have developed an almost fascist obsession with the trinitaria, in particular Duarte. All the coins have his image, the highest mountain is called Pico Duarte, there is a bust of him in every school, most public buildings and every town square. There exists a Instituto Duartino, to promote patriotism in society. This obsession has led to a distinct lack of imagination in street names. In Santo Domingo there is a least one Calle (street) Duarte, Avenida (avenue) Duarte, Autopista (motorway) Duarte, Plaza (square) Duarte, and I am convinced there might be more than one of each. Added to the number of addresses involving Trinitaria, Mella, Sanchez, Independencia, and 27 de Febrero, and it is easy to get lost. If someone tells you to go to the corner of Independencia and Duarte, this could mean any number of places in the city. It has confused me more than once.

If someone who you don't like calls you up and wants to meet, just tell them that you will meet them at the statue of Duarte, on the corner of Independencia and Trinitaria.

Of course, I could use this opportunity to expand on Dominican national identity, but I am lost and trying to find my way home.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

The standard drink is a Presidente, the local half-decent brew. The company also makes a second beer called Bohemia, which is also OK. The third beer available is Brahma, a brazilian beer that tastes like meado de gato. Otherwise groups go for a cuba libre servicio, which consists of a bunch of plastic cups, a bucket of ice, two cokes and a bottle of rum. Admittedly the high sugar content is about as intoxicating as the alcohol, but when in Rome.....

This weekend, we followed this up with a trip to one of the better colonial zone bars. There are a few too-cool-for-school yuppie bars, the type with water features in the window and aggressive air conditioning, who would rather serve rubbish imported Johnnie Walker than good local rum. However, next door to one of these is a great establishment called El Sarten, (in Hostos, if you are ever in town), which is a tiny bar that serves cold beer, but that plays amazing old style Son. Many people, because of Buena Vista Social Club, associate this Latin Swing with Cuba, but its origins are as Dominican as they Cuban. This tiny bar is always jam packed, but there are still plenty people dancing, young folk dancing with 80 year old men who still bust some great moves. The standard of the dancing is amazing, until I was forced to get up and give it a go. I tried my best, nobody cared that I didn't have the natural fluency and style of the Dominicans, and was told "Oh well, give it a bit of time and you'll get it eventually"

The Cuba libre servicio dampened the pain somewhat.

41st most elegible woman in Scotland

And that is official!

Friday, November 17, 2006

They are basically wheelbarrow with a bike attached, so if business is slow, they pedal off elsewhere. You frequently see these guys pedalling 30kgs of tropical fruit down a 6 lane highway. Note the high-tech cooling and shading sytem, and the cutting edge brake.

1. A few months back, the high prices charged by power companies, combined with city-wide blackouts relating to poor infrastructure investment led to demonstrations and riots. The police then shot 7 unarmed protestors dead.

2. Last year there was a prison riot in an overcrowded jail. During this a fire broke out, and 140 prisoners burnt to death.

3. A captain in the army was arrested, on the request of the US, on drugs charges. He was caught with 1,380kg (that is not a typo) of pure cocaine. Because of the bribes he had been passing out, including funding local hospitals and schools with drugs money, locals tried to break him out of jail. As the army is heavily involved in the arms trade, and because he had donated large sums to the two main political parties, this man had been known about at the highest level for a long time, but no one did anything until the US forced them to.

Now, if story 1 had been Bolivia, story 2 had been Brazil, and story 3 had been Colombia, then the BBC and the major newspapers would have mentioned it, if not covered it in detail.

All three occured in the last 2 years in the Dominican Republic

There seems to be a complete blackout of reporting of Dominican Republic stories. Numbers 1 and 3 weren't even mentioned on the BBC website, and number 2 had only a short story, half of which was taken up by references to smaller prison riots and fires in Brazil that killed fewer people. There is a great deal of fascinating stuff going on here, more interesting than much of Latin America, but the DR just isn't on people's radar. There isn't an image in Europe of what the DR looks like, other than a tourist destination, so it is difficult to communicate. We all have multifaceted images of Brazil, combining football, good looking women, beaches, the Amazon, favela slum-towns, violence etc. Our image of it is such that we can cope with top footballers and slum-town violence coming out of the same country, but with the DR it is a cheap holiday destination with all inclusive resorts, and we don't know much more about it. The European media couldn't manage to talk about rampant army-run drugs trafficking in a country rarely mentioned outside of a Thomas Cook brochure.

I reckon most people who go on holiday to the DR from the UK couldn't point it out on a map, and that is sad, because it is a fascinating place with lots of crazy things for geographers to get stuck into.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Of course, this is linked to the secret insecurity that every PhD student has, the fear that some day they will be sitting at their desk, and the vice-chancellor, flanked by the head of deparment and supervisors, will rush in and denounce you as a useless fraud who has no right to be at the university, and has fifteen minutes to clear their desk. Every PhD student constantly has moments of self-doubt about their ability and direction of their work, but they are amplified ten times when on fieldwork, a combination of culture shock, language problems, and the shift from theoretical speculation to data collection.

Admittedly these feelings have diminished significantly as two important interview subjects have set dates to talk to me. Typical law of averages, just as soon as you are getting fed up of plodding along without getting anywhere, you find out something important.

I definately haven't reached the stage I was at during my last strech of fieldwork. Then I was pretty down about my work, and at one point resolved never to do fieldwork again. Cue sixteen months later..... The big difference is that this time I have much better ideas about what my research is about, my aims and questions are much better defined, and I am generally more prepared. Also this time I am here for much longer, so I have to accept that I am living here, and can't try to drift through it. This entails a totally different mindset to short term fieldwork, and most people tell me that paradoxically the feelings of fieldwork blues are much less acute in long periods of fieldwork, because of this different mindset.

My advice to people who want to go on field work is:

- Thoroughly prepare your ideas and research questions. Don't have the attitude that you will work it out when you get there. Of course, the better defined your questions are, the more likely it is that they will change, but at least you have something to work with. Always have a plan that can fall apart.

- Accept that you will be there for a long time, and bloomin' well act like you are living there

- Go somewhere nice. Caribbean comes with positive recommendations from me! If the funding councils are paying you to go somewhere, you might as well go somewhere good. My friend Charlie originally proposed to do work in the Scottish Islands, thought about it, and then moved her research to the South Pacific - smart girl!

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

As I am sitting in the house, drinking the day's first cup of fine Dominican coffee, I make sure that I have enough small change to get me to wherever I am going. I live very close to the old colonial zone, about 40 yards from the square that is a bit of a transport hub, but I have been working in the periphery, about 7 or so miles away.

There are two types of public transport in Santo Domingo: Carros publicos are cars (for some unknown reason 90% of them appear to be 15 year old Toyota Carollas), with a driver licensed to run a particular route. These travel up and down the main arterial routes of the city, and will take you any distance for 10 pesos (about 20p). To stop one, you need to give the right hand signal - waving a finger means that you want one going straight on, pointing sideways means that you want one turning right, and a thumb means one turning left. Confusingly, different hand signals are used in different routes, so I always check by asking the driver if he is going my direction. This sorts out any potential problems, apart from the time when I confused the cemetary (cementerio) with the cement factory (cementera) - unless I wanted to get buried in concrete. Be warned, the official capacity of these nominally 5 seaters is in fact 7 full grown adults and any luggage that they may have. Two people share the front passanger seat (if the person on the door side is rather large, the person on the inside might find the gear stick curiously uncomfortable), and four squash on the back seat, plus driver. Not confortable in hot weather on terrible roads, especially when there are small children, who sit across people's knees. Once I was in one of these publicos with maximum adult capactiy of seven, as well as two children, one of whom had a live chicken in a cage on their lap. Today was less interesting, just someone's four foot artificial christmas tree stretched across our laps.

It should be mentioned that these generally have the windows wound down to allow the breeze to circulate, along with dust, pollutants and anything else in the air. They almost always have a cracked windscreen, held together with tape, and so many dents and scrapes they look like they have been made from scrunched up tinfoil. I was once in one of these when the bonnet was blown off by an explosion in the engine, which emitted vast plumes of acrid grey smoke. The driver charmingly apoligised for the inconvenience, and promptly refunded us as we were pushing the flaming wreck to the side of the 6 lane motorway.

Despite the discomfort endured in these journeys, I rather like them. Firstly, the people are always in a good mood, never complaining about being squashed up to a 16 stone man with bad body odour and a live chicken. They greet everyone as they get in, and chat or sing along to the radio. They even tolerate envangelical preachers, who try and save their soul on their way home from work. Secondly, the drivers manage to get some wonderful performance out of these old bangers, weaving in and out of traffic, squeezing at 40 miles per hour through gaps that leave and inch on either side, just to be as efficient as possible and process as many passengers as possible. Dominicans use the horn rather liberally, as no one ever indicates with flashing lights - they just beep to tell people they are manouvering, and then move. There are subtle differences in beeps, a dialect almost, telling people that they are turning left or right, that they are impatient in traffic jams, or they are trying to attract the attention of the attractive girl walking past.

The other type are guaguas, equally beat up minibuses, usually with the doors taken off for easy access. They work in teams of two, a driver and a cobrador, who deals with passangers. They hang out of the moving vehicle shouting out their route. Sometimes I look for shouting "feriadoceferiadoceferiadoce", meaning that they are going to the Feria, the district with government offices, before heading to Kilometro Doce, another transport hub. Other times I look for "chuchichuchichuchi" meaning that they are travelling up Avenida Winston Churchill, a collection of anglosyllables unmanagable for the hispanophone. Again these have liberal attitudes towards maximum capacities and seating arrangements. At busy intersections and areas of slow traffic, people will grab hold of the outside of the bus, standing on the wheel arches, trying to sell biscuits, water or fruit to the occupants as the bus drives along.

The great thing about this system is that with certain knowledge and suspension of ideas of personal space, one can travel from one side of the city to the other cheaply and quickly. The traffic is very bad at the moment on my main route, as there are whacking great holes in the road and closed sections, forcing drivers to take detours down side routes. These holes are tunnel excavations for the Santo Domingo metro, part of the government's drive for a Developed, Modern, Progressive Nation. Although there are many cases of egotistic grand projects in the Dominican Republic's history, this one seems like a good idea. Whether it will work, given life and electricity supply here, will have to be seen, but it should do wonders for the massive polllution on the roads. The guaguas and publicos will probably survive, and people will just squash up and socialise in the metro just as they currently do on the roads.

Monday, November 13, 2006

I have spend the last two and a half years working on developing hypotheses and theories about what the world should look like, and it seems determined to prove me wrong in a rather spectacular way.

Aparently, it is called "making progress in your research", although what it is going to progress to is as yet unknown. It is incrediably frustrating, as have spent months working out in minute detail what current thoughts and theories suggest the world of conservation politics should look like. And it doesn't resemble it at all. I would tell you what it does look like, but I would probably get sued. You'll have to wait for that one.

On the plus side, my work therefore has the capacity to contribute something new to academia. A physical geographer friend of mine says that you know that an article is human geography, rather than sociology or economics because it contains the phrase "this work challenges important assumptions...". It is a phrase that we do hold dear, and love to use at any opportunity, in the same way that anthropologists prefix most things with "meta", and cultural theorists use "post". I could probably do well as a cross disciplinary academic by talking about "this work challenges post-colonial meta-assumptions...." . At the more boring conferences, I am sure there are sweep stakes on how long it takes this phrase to appear in presentations (other suggestions for academic catchphrases welcome). Therefore I can assert my claim to be a human geographer as I now have not only an assumption, but a newly discovered challenge to it.

The reality of this is that the work seems incrediably frustrating. It has been my full time job for a whole year to develop ideas and write literature reviews, essays and research proposals, and for this to be (partially) torn up in a few days is depressing. If I was told when struggling over my literature review that most of it I would later reject, I might well have become more dissolutioned than I ever was. It does seem that all that reading, thinking and writing was a waste of time, but I am sure that my colleagues will remind me that it wasn't, because I am now in the position to know when I am wrong....... as Donald Rumsfeld so nearly said.

Update: Just recieved this in an email from supervisor: "Always a good thing to have as many of your expected ideas to be refuted as possible on a phd. Its a sign of thorough preparation (for without it you would not have made such detailed refutable speculations in the first place). "

Still doesn't make me feel better.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

I suppose one of the most irritating things about doing fieldwork is that the food is terrible. I am currently in a rented apartment, but as the gas isn't working I can't cook. Given that I was in a hotel for the first week this means that I haven't cooked anything since arriving here, apart from making the odd tomato and coriander salad (but that doesn't really count).

I have therefore had to live almost entirely on street food. Given that I am somewhat obsessed with things culinary, this has grown to be rather depressing. On the plus side, the combination of street food, a hot and sweaty climate and developing world hygiene means I am developing an immune system that could survive a plague epidemic. I would give a list of foodstuffs that I really want, alongside details of what I would do to obtain them, but it would be a thouroughly upsetting business.

As much as academics rant on about positionality, methodology and suchlike in research, surely it is the radically mundane things like wanting something that tastes of flavours other than salty grease that affects how you go about your work. I can predict that a constant theme of this blog in future months will be the way that research training tells you the obvious about positionality and the irrelevant about methodology, and how this is only exceeded by the way it ignores the everyday emotions of fieldwork.

Admittedly, part of it is written in frustration about going to Caribbean studies conferences and seeing yet another presentation on Jamaican poetry. I remember one incident at a globalisation conference for postgraduates, when I introduced myself to someone working on banking in Trinidad. I was told that the Dominican Republic wasn't "the proper Caribbean".

When talking about the Caribbean:

- Talk about cricket, strong accents, reggae, and the Windrush. Ignore the fact that the four biggest populations in the Caribbean are Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Puerto Rico. Therefore don't mention baseball, Spanish, merengue/bachata/son, or about Cubans in Florida and or 1,000,000+ Dominicans in New York.

-All sentences spoken in the Caribbean end in "yeah mon". Ignore the fact that English is only the third most spoken language in the Caribbean. Don't mention the Dutch or Danish Antilles (come on, how many people know there is a Danish Antilles?)

-The caribbean is a selection of small islands that are all close and similar enough so that they can play as one cricket team. It is not a group of islands over 1000 miles across, with a total population of over 30,000,000, and a huge variety in size, wealth, culture. That it sits in a wider basin surrounded by Latin America and the US, with their economic and political influence is mere details.

-Any article with anything negative to say about the Caribbean by law must have "Trouble in Paradise" as part of the title.

- If you are going to mention Haiti, make sure you mention Voodoo, as there is nothing else there. Voodoo is a bizarre mystical magic (not a religion), that involves skulls, ceremonies in cemeteries, and crazy ancient old witch doctors. Voodoo is not an off-shoot of catholicism involving patron saints and middle class businessmen. Voodoo dolls do exist outside of Hollywood.

-Caribbean people leave on decomissioned troop carriers to go drive buses in Birmingham. They don't leave in overcrowded sailing boats in the middle of the night, running risk of drowning to become an illegal immigrant washing dishes for $3 an hour in New York.

-Any mention of the Hispanic Caribbean should be limited to Cuba. Remember that Cuba didn't exist until 1959, except in Hemmingway novels. All mentions of Cuba must talk about delapidated old buildings, 1950s Chevrolets, Buena Vista Social Club, Fidel Castro's longevity, and possibly the US blockade. Every sentance should include the following words or phrases "Revolution", "a bygone era", "cigar", "in defiance of the US", "beard". It must be accompanied by a photo of Che Guevara smoking a cigar or of a 1950s car. It should not mention poverty, lack of human rights and freedoms. Everything that happens is romantic, accompanied by a smiling singing old bloke, some dancing and ends in a nice cigar. Ordinary mundane things don't happen.

-Feature white sanded beaches, turqouise seas, coconut palms. Don't mention rain forests, alpine forests, big smelly overcrowded cities.

-Talking about post-colonialism is essential. In fact, everything in the Caribbean can be explained through post-colonialism. Post-colonialism is the grand unifying theory that determines everything that occurs in the Caribbean. The most important factor in society is post-colonialism, and so post-colonialism's influence on society should be mentioned at every possible opportunity. All that caribbean people do all day is to find their new post-colonial identity, through writing poetry and painting.

It is critical to make sure that the colonialism involved Oxbridge graduates who brought cricket in exchange for sugar, and ended in the 1960's. Christopher Columbus is irrelevant, as is Simon Bolivar, Jose Marti and the 19th century. When mentioning post-colonialisms influence on Caribbean society, remember that trade agreements, IMF and US influence, and all other things that pass in other areas for important structural influences are mere details.

-The main exports of the Caribbean are Bounty bars and rum.

-All Caribbean people are black. There are no shades, European heritage, mulattos, complex racial politics, racism, or Chinese immigrants.

-Caribbean people sit in beach side shacks, selling coconuts whilst listening to reggae whilst avoiding the stresses of the world - this called living a simple life. Talk about relaxation, chillin', but don't mention poverty, unemployment, lack of power, safe water and sanitation.

-Pirates were bearded people who had all sorts of adventures. They didn't sell DVDs on street corners. Crime in the Caribbean involves boarding ships with cutlasses, in search of buried treasure. It doesn't involve murder, violent robbery, corrupt officials, or bribing police officers. Always mention the eyepatch and parrot.

Don't get me wrong, there are many expats here who meet a girl and have a relationship that is more than financial. Although there are plenty of girls known as "buscavidas", or looking-for-a-life, more interested in the colour of their man's passport than his personality, there are certainly lots of happy trans-national families here. However, there remains a common assumption that a foreigner travelling on their own must be looking for a more intimate experience of local culture.

The sex tourism thing is a funny one. There is quite a specific geography to it, as the different villages around the different beach resorts specialise in different types of relationship. If you are in the know, you arrange your holiday at one specific hotel if you are a man looking for a stunning younger lady, another if you are a lady after a man, a man after a man, or woman after a woman (although I have been told plenty about the other three types, I am yet to hear of stories of international lesbian sex tourism. I am also aware that those last four words of that sentance may bring some interesting and probably soon to be disappointed google traffic in the way of this blog). There is undoubtably a geography PhD to be written on the subject, though mine is not going to be it.

Thinking about it, the sex tourism business is probably the Dominican industry most in tune with customer needs, and as any business entrepreneur will tell you, that is why it is the most succesful.

Some of you were probably waiting to see if I would post on this subject.

Friday, November 10, 2006

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Number one - never have a proper visa. If stopped by police, explain that you a tourist who has lost their tourist visa. This gets you more respect, and less likely to be asked for a bribe.

Number two - when you get your passport photo taken, always wear a suit and tie. As I was told "you never know when you are going to be crossing the Haitian border, in rags and with a 10 day beard, and you need to be taken seriously." Useful advice for everyone, I think.

Number three - as the police are always stopping motorists 'for having a dirty car' and 'fining' them (any excuse for a bribe), then if waved over by the police, just give them a smart military salute and keep on driving. They are then in two minds - is this person really a police or military person, or am I going to get in trouble for stopping a General? Apparently, it works every time. When you are not in your car, just flash any official looking document at them - they are generally illiterate and if you do it with confidence, they are not going to challenge you.

Number four - if anyone asks you were you are from, say China. As the geographical knowledge here is so bad, then they are not sure whether you are having them on, as they kind of know what a chinese person looks like, but are not too sure. They never challenge your chineseness. This is not really for avoiding trouble with the law, but it is great fun to see the confused look develop across their faces.

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Today's experience was Dominican public service at its very best. Having arranged an interview with the secretary of someone at the national parks office, I arrive to have them tell me that they have never heard of me, and that I should really speak to their colleague, who will be back in January. Not wanting to waste the effort I went through to get out to the office, I then head to the park services library archives (the three bookshelves in the basement). Having asked for a copy of the budget and annual report for the last 5 years, the reply comes that they think they have something to do with budgets from 1982, and will this do? It didn't matter anyway, as they had no idea where it was.

To make up for this, I try to go to national statistics office, to get hold of the budgets from them. Turned down by the doorman for not wearing a tie. Seriously. It certainly says something about the stupidity of the bureaucracy that archives are harder to get into than swish nightclubs.

The flip side of this, and the thing that makes this country such a fascinating place, is that people outside of officialdom are more than willing to share experiences and help each other out. At this time of year there is a huge rainstorm at about 4pm, which starts with some threatening clouds, a few drops which are promptly followed by rain so hard it hurts. Everyone runs for shelter. The trick is at precisely the right moment to be walking past somewhere with a large overhang and cold beer. The folk round here learnt that a long time ago, and this need is amply catered for. Everyone just gets chatting, the younger folk start flirting, and the older folk start taking bets on the outcome of the flirting. People are generally interested to chat to one another, something you would never see in the UK. They are often absolutely hilarious, more of which I am sure will come.

Through such a random incident, someone referred me to an American lady running bird watching tours in the south west. The Dominican Republic is a paradise for birds (an endemic and endangered species of parrot breeds where I am currently staying, and if it keeps on depositing just near where I am walking, it will shortly become more endangered), and lots of migratory species overwinter and breed here. A quick chat turns into a two hour conversation, the loan of a number of books, an invitation to spend a weekends birdwatching and a dozen phone numbers and contacts I should follow up. Plus I am now renting a room from a internet contact I meet up with for a quick chat about national parks.

The road traffic still makes me laugh. Today's sight was a fresh faced traffic cop directing traffic whilst chatting to his mate on his mobile. He was still blowing his whistle as he talked, so the friend was either very deaf or very patient. Suddenly bearing down on him at 40 mph come a dozen police motorcycle outriders and five big blacked out 4*4s - the presidential motorcade. The poor boy doesn't know whether to stop the traffic, salute or what. In the end, he just ignores it as if this huge kerfuffle wasn't happening. The president speeds through, and life continues once more.

The people you meet in hotels are generally a bit more interesting than your average. Meeting the ubiquitous, and rather charming, Australian on the ubiquitous world tour was followed by a rather senior Dominican expat who had returned from New York for 10 days for some “f****n’ and suckin’ with some of my girls”. Bit tongue, crossed legs and winced.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Still, thanks to increased expenses budget, I am not in the same old brothel, but in a proper (cheap, backpackers) hotel, and the best bit is that it doesn´t charge by the hour!

Tried to spend some time in the National parks office archives department (i.e. a room with three bookshelves, and a bored teenager talking loudly on a phone). The parks office is literally in the middle of a slum town on the edge of the city. Major traffic headache to get to. Really, smelly dirty horrible place, ideal for creating plans to protect beautiful rainforests. Anyway, there appears to be no indexing system, and the folk who work there clearly only got the job because they have the right connections, and are less than useless. Still, am off to the national statistics office on tuesday, so lets hope things are better.

I then proceeded to get slightly drunk on rubbish beer outside of a corner shop, chatting to the boy who works there about how he is trying to save 80,000 pesos (about 1,600 sterling) to pay for the illegal boat trip to Puerto Rico, where he is going to work as an illegal immigrant on a building site, before going to New York. These two incidents show what is holding back this country, that the only way to get forward is to either work as a corrupt public official, or to leave and go to the US.

Sight of the day: A seven tier baby pink wedding cake being driven at high speed through the streets, on top of a rusty van, with two blokes hanging out of the windows to hold it down. I am never surprised but always amused by Dominican Transport.

Ah, beautiful Santo Domingo, so glad to be back.