The bizarre experience of going across the world to find out strange things about strange places. My experiences of fieldwork, and life in the Dominican Republic

Sunday, December 24, 2006

- A quick note to anyone who might be travelling in rural Dominican public transport, especially during busy periods. Bring plenty of caribiners so you can clip yourself and your luggage to the side of a pickup truck. Particularly important if your driver likes to take hairpin bends at speed, as I have seen luggage, although not people, thrown off the side.

I am glad that I finally caved in to advice and came down early. The roads were heaving with traffic, and every guagua had luggage on the roof, and people hanging out of the doors. My own journey took a bit longer than usual, not just because of the traffic, but because we got a puncture and also the engine exploded in the middle of the motorway. Our handy chofer fixed the thing in 5 minutes, Dominican style, with bits of electrical tape and an old t-shirt. A bit like Blue Peter on acid. However, the traffic wasn't too bad heading into the city, as most Dominicans go to stay with their family in the campo for christmas. Outbound traffic was horrendous, with big queues for guaguas.

I am a bit miffed at missing the party though, as I was assured of a good time. They were going to do a giant sancocho, a traditional stew, enough for the whole village. This was to be followed by the annual angelito, where villagers exchange gifts, having picked a name out of a hat a few weeks back to decide the victim of their secret present. Lots of individual households were also going to roast a pig over a fire - on Saturday morning at 7AM I was rudely awaken by the deafening squeals as my neighbours slaughtered their swine. They then gutted it and shoved a big pole through it to hang over the flames. There was a surreal sight of several pigs-on-a-stick lined up outside the corner shop. The rest of the night was to be taken up with dancing, and several ladies had promised to show me how to strut my stuff, Dominican country style. Tragically, I am going to miss this, but it's my birthday in a few weeks, so perhaps I will get a dance then.

Whilst in Santo Domingo, I am going to have an orphans' christmas with all the other foreigners I know who don't have enough money to fly home and see their family for christmas. Feliz navidad

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Of course, in all walks of life, one has to accept that not all people have the same opinion as you, and that you must respect that. However, there are somethings that are harder to cope with than others. In particular, I do get shocked by the way children in my village get treated.

Of course, children here are certainly well loved, and the intention is most definately there to take care of them. If their parents are out working in the fields, the children are passed around neighbours and relatives in a way that perhaps a lawnmower or a really good novel is passed around in UK society. Like lawnmowers and novels, they are given a lot of attention, then returned with a slight smudge from an unrecognisable source.

Perhasp it is because my own mother has spent so many years working in public health, but I do struggle to restrain my moralising tongue when I see what they feed their babies. Most women in the village have their first child age 15, disturbingly often with their cousin. It seems that breastfeeding is virtually non-existant, instead mothers go out of their way to feed them with powdered baby formula. I don't know if this is because like many other things in the DR people automatically assume that a shop-bought 'American' product is better than the indigenous or natural product, or if it is for far more controversial reasons. Like almost all other universities in the UK, my employer has banned all Nestle products from its union shops, on the basis that Nestle is aggresively marketing powdered baby formula over breast milk, the natural option being better in 99% of cases, with the risk in formula of illness from dirty water, and therefore putting company profit over babies lives. The water in the village is exceptionally clean, though not flawless, particularly for young babies with weak immune systems, so the issue becomes the relative expense and the absense of nutrition and natural antibodies when missing the natural product. This boycott of Nestle is a central tennet of the right-on thinking that dominates student politics, but it is also a view that I have some sympathy with, given my own experience.

Out here in the campo, all of the colmados (village shops) have some brand names painted on the outside wall, so the casual passerby can clearly see what this shop sells. Common brand names include Presidente beer, Verizon phonecards, and Nido, a Nestle baby formula. I don't

know if Nestle have paid for these signs to be put up, or whether this constitutes an aggressive marketing campaign that turns mothers off breast feeding, but it is certainly grounds for suspicion. For once, I think I support the right-on thinking of the wannabe parliamentarians in Student Unions across the land.

It would be far more challenging for these people to incorporate some of my other observations into their thinking, as some of the other stuff people here feed babies cannot be blamed on ruthless international capitalism. Seeing a three month old baby given sweet coffee and sugary soft drinks, and a four year old given neat rum to drink shocks me. I can bite my tongue many of the other things that go on here, the views on Haitians and so on, but I really struggle from criticising my friends when they feed such stuff to their babies. I can try and formulate academic reasons for it, such as a developmentalist discourse that automatically assumes that 'modern' products are better than 'traditional' or 'natural', but it is no use. So far, I have managed not to burst into a lecture, though I did in another village when I heard the shockingly ignorant views of a local teenager on the causes of AIDS, and how to prevent it. I felt it was my moral duty.

Talking of babies, congratulations to C and S on the arrival of M!!

Warning: This blog contains infantile humour and references to animal cruelty.

After weeks of failures, when I arrived late on the scene to find only blood and feathers, I finally saw my first cockfight, an important part of rural Dominican life.

I wanted to see a cockfight partly because of the brilliant essay on Balinese cockfighting by Clifford Geertz (anthropology great of the 60s/70s), where he finally got accepted into his village after months of trying when he got busted by the police attending an illegal cockfight, but mainly I was driven by curiosity. I didn’t really need to attend a cockfight to become accepted in the village, as my fast spreading reputation regarding my inability to dance even whilst sober sorted that out - people are telling me all sorts of wonderful secrets after only a week of knowing me.

The first fight I saw was one on a little side path off the village road, rather than one at the cockfighting arena (i.e. shack) down the road. Such fights are used either to train novice cocks so they are ready to fight on the main stage, or to fight the weaker chickens who can’t handle the fiercer competition at the arena. Despite this being the second division of cockfighting, the handful of observers still got pretty excited by the whole thing.

It starts with two people with their cocks in hand, stroking them and eying up each others’ for size. They then set them on the ground and let them loose for a few seconds only, to see that both are in the mood for fighting and won’t run away. Regulation spurs are fitted, a designated timekeeper is set, and the chickens are let loose. I am not sure I understand the exact rules, but it is not just a simple matter of two chickens pecking and scratching each other to death. At the arena, where fights are every Sunday afternoon, the rules are stricter and written into Dominican law – there are even weight categories like in boxing, though there are perhaps more featherweight and Bantamweight categories in cockfighting.

The fight was a lot less spectacular than I expected. Cocks stare at each other for a few seconds before a flurry of wings as they peck at each other’s heads, slash each other with the spurs, or pin the other down with their wing to make pecking or slashing easier. The occasional feather or drop of blood splashes around, and after twelve minutes, a winner was declared. The proud victor was cleaned and petted by its owner, whilst the loser was dispatched for soup. Apparently it makes a particularly rich soup, the adrenaline released in the fight giving a distinct flavour to the meat.

Cockfighting is a crucial part of Dominican rural life, and an area that I am yet to scratch the surface of. The champion cock breeder in the village is an eighty two year old man, who is rarely seen without a cock in hand, and who mumbling to me how cockfighting is a reminder of life, struggle and death that is important to him in his old age. Certainly the cockfighting culture is much more than a simple exercise in sadism that it might be portrayed as. A good cock is described as being “brave” rather than strong, and there is great admiration for the many cocks who refuse to give up and fight vigorously to the very last.

After living a year in

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

When I have been making enquiries about relationships here, everyone keeps telling me "we are all family here", and they are certainly not lying. The easiest way I can put it is that it is a 'limited' gene pool. Everyone seems to marry their cousins and the family trees are soon resembling plates of spagetti, with links in places which are as surprising as their are worrying. Unfortunately, one does not have to look closely to see that this lack of genetic diversity has had some clear effects on some individuals.

Despite my community being a stereotypical mountain village, I am rapidly becoming more certain that I prefer being with these people than with your average Santo Domingo resident. I can never do an interview or even walk past a house without being invited in for a cup of coffee and a blether, and often I get given a plate of rice and beans during any interviews I do at middday, without even being asked if I am hungry. It takes me so long to do the tasks that I set out for myself each day, simply because I get distracted by another unplanned conversation. I rarely complain because these almost always give me some more information on life in the village, revealing a previously hidden aspect to life in this close community.

The village is strung out along the road, with my shack being at the extreme of one end (technically in the next village, but they forgive me for that), and the other end of the road is 3km away. Despite this being a relatively short distance, I find myself using my motorbike to go to meetings at the other end of the village, simply because I know from experience that if I go by foot I will probably not make it, as I will be distracted and delayed by another cup of distressingly sweet coffee.

I did go to the Shakira concert last night, which was an excellent show, but my blood pressure is too high to tell you about it, following the disgustingly inconsiderate behaviour by spoilt middle class Santo Domingo brats. As my friend commented "it was a great concert, but it was a shame it was in a stadium full of the rudest people on the planet". The best moment was when Shakira informed the stadium how much she loved being in Santo Domingo, just as divine comedy intervention chose that moment for the power to go out - "ah, we have a problemita", she commented. How true, how true.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

For example, the American embassy is a big sprawling complex covering several blocks of middle class Gascue barrio. The embassy, the consulate and the international aid buildings are all surrounded by three metre high concrete anti-car bomb walls, policed by severe looking chaps with big guns. They recently staged a three hour unannounced "anti-terrorism" excercise, waking up middle class slumberers at 6 AM on a saturday with armed troops running around, blocked streets, smoke bombs and the like. I know there is an anti-yanquista movement here, but they are a bunch of students who couldn't possibly pose a security threat.

I recently interviewed a senior official at the international aid branch of the embassy. It literally took me half an hour to get through security, they confiscated my passport, my laptop (after taking down the 27 digit serial number, for some reason), my mobile phone, and misteriously my pencil case, which James Bond style actually doubled as a high explosive anti-tank device. So just as well the bored security man took that off me. I had to pass through the metal detector twice (once would normally been enough, but theyhad forgotten to switch it on, so I had to do it again). I then passed through into the embassy to meet my interviewee, who then informed me that it was a bit stuffy inside and he would prefer it if we went across the road and sat in the park to have our chat. I gave the security man a dirty look as we walked past into the park, with its tweeting birds and members of the Caribbean branch of al-Qaeda behind every tree. Last week I ran into members of his family in the mountains where they were having a weekend camping. Makes a mockery of the situation.

The French embassy, like the Italian, Mexican, and Trinidad and Tobaggon representations, is house in a grand colonial mansion. It is an elegant, refined edifice that once was owned by Hernan Cortes before he went conquering Mexico and looking for El Dorado. It may also have been the house of Ponce de Leon, before he off to Florida to find the fountain of youth - it was unsuccesful as he died of typhoid in the first few months of his trip. Whatever he drank, it wasn't the fountain of youth. I think the French embassy has been there ever since, and it exudes a gallic air of snobbery.

The British embassy, for some unkown reason, is in the seventh floor of a decrepit insurance company in a depressing shopping district. It is truly a half-arsed attempt. There is no sign at street level to inform you outside the representation of Her Britannic Majesty's Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and you have to take the lift as the stairs have fallen down. Once you get into the building, security is minimal - the job of the security guard is merely to politely request, if you don't mind, to do something that goes against every part of the Dominican psyche, and turn off your mobile phone and wait your turn in the queue. How marvelously British.

I forgave their choice of location after that, and was only slightly disappointed not to be offered tea and crumpets.

Monday, December 18, 2006

In case I haven't told you, I have christened my bike in tribute to Che Guevara's bike in The Motorcycle Diaries: His was called El Poderoso (the mighty one), and mine is now known as La Flaquita (the weakling). She has certainly been struggling to get up the main road that travels into the mountains where I live, which is four thousand vertical feet of hairpins and potholes.

It is a veritable lesson in tropical biogeography that would delight old Professor Furley. At the start, as you climb out of the rice and tobacco growing plain of the Cibao, the roadside trees are dominated by cocoa small holdings, with red and yellow cocoa bean pods hanging from the branches. Further up and the smallholdings get too cold for cocoa, and turn to coffee, grown in the shade of many trees that I know neither the spanish or english names for. The slopes are very steep and very green, different shades but always at about 50 degrees to the horizontal. As you rise, you do so along with the air brought in from the Atlantic, which cools as it rises, leaving an almost permanent blanket of cloud at around 3000 feet. This is too cold and wet for coffee and other cultivars, so are dominated by Magnolia, with epiphytes growing up on the branches. This is prime territory for orchids, and there are some species that are only found on this particular slope. Further up and the air gets truly soggy, so that the top of the pass is populated by tree ferns. I notice the vegetation more on the way up, as I crawl up at walking pace, the engine squealing away. On the way down, I am too busy looking at hairpins and potholes to notice the trees. Just at the very apex is a shrine to la Virgen, and people either stop to light a candle or cross themselves as they pass it. This is either to give thanks to their engine for putting up with climb or to ask for divine protection before diving down the descent.

I live just in the lee of this pass, so while not quite as cold and wet, I am still woken up in the mornings by the sound of rain on my corrigated iron roof, to see my breath in the air. It takes a few cups of coffee before I remind myself that I am in the Caribbean.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Women here seem averse to wearing anything that doesn't have at least a three inch heel. Indeed they prefer it to be five inches, and platform. The shoes must not be simple brown or black, but must be a bright colour - flourescent green appears to be 'in' this season. A Santo Domingo lady chooses her clothing by starting at the feet, and working up, making sure everything is matching. Even Joan Collins couldn't out-powerdress these girls. The heels should be as loud as possible, so that not only do you tower out from the crowd on six inch height extending stilletos, but everyone will hear you coming as you clack-clack-clack along.

I hear that the fashion for flatform and high heels dates back to Rennaiscence Venice, where what was a practical measure to avoid getting wet feet on the flooded cobbles of St Marks became a way to get one over the rest of the society girls. The competition to have the highest platform shoes grew to such a height that they topped thirty eight inches, and having such an extended centre of gravity, the women had to walk with a servant on either side to support them as they waddled along. It was all worth it, as not only did you show that you were rich enough to buy ridiculous high heels and to have two servants to help you, but it showed that you were so separated from having to earn a living through work that you could strap on such ridiculous footwear as you pop out to buy a pint of milk and the paper. Santo Domingo women always make sure they are wearing innappropriate footwear when pushing the supermarket trolley.

You must bear in mind that Santo Domingo's streets are irregular, full of potholes, broken pavements, dogs, street vendors and other inconveniences. I struggle to walk aroun in my oh-so-sensible trainers, yet these ladies seem to manage fine. They get in and out of public transport wearing them, althought they do it subtly so that people don't notice that they are dismounting a guagua rather than a yipeta. It appears that the only thing worse for ones social standing than not being in ridiculous footwear is to fall over in heels. It has made me wonder if there is a kind of Darwinian process at play, whereby through natural selection Dominican women have developed a type of femur that can only function if supported by a towering heel, rather than flats. I have extended this idea, and decided that Dominican women who fall over in heels are treated like racehorses who fall and break their legs - they are shot and boiled down for glue.

Dominican men are no means less fascinating. All men, no matter what their position, must have immaculate black shoes. Even the people who I know struggle to pay the bills will always leave the house in polished black shoes. The shoes may be full of holes, the sole worn out, but they will be so polished that you can see your reflection. This is all the more surprising when you consider how dusty Santo Domingo streets are when the weather is dry, and how muddy they are when it rains. Providing a mobile service in maintaining one's mirrorlike lustre to one's shoes is the small army of shoe shine boys. These guys run around the city with an empty 5 litre oil can and a small box contain the tools of the trade. For a few pesos they will sit on the oil can with your foot up on the box, and restore the glossy finish with professionalism and care. Budding little capitalists.

I get away with my practical, dependable, dust coloured trainers because I am a gringo, and therefore am not expected to dress decently. God forbid that I would wear flipflops though.

Just to put you in the picture, I have spent five weeks working in a huge, bustly, polluted, noisy, 24 hour, sociable city, living in a great apartment with somebody (an American) who I can relate to when I need to be less Dominican, but who knows such a huge amount about the culture here that they have a source of many a great pointer. I have also had wireless internet access, permanent mobile phone coverage, reasonable electricity supply and a water supply that only works half the time, but at least I know which half it will or won't work. I will move from this to a tiny shack in a small mountain village with a few hours a day of unpredictable electricity, no running water, a half hour journey to pick up mobile phone coverage and important text messages, no water and a bunch of campesinos who I am sure will be welcoming and friendly, but who occupy a different world from myself. In a strange way, I feel that Santo Domingo is far closer to my world in the UK than it is to the mountains, even though the geographical distance is 100 miles rather than 8,000.

However, I know that I have lots of work to do up there, and that will keep me too busy to feel isolated, and that I need to be back in Santo Domingo on the 19th for the most important meeting of this trip:

I am going to a concert featuring Columbia's second most intoxicating export, Shakira. And I can't wait.

Monday, December 04, 2006

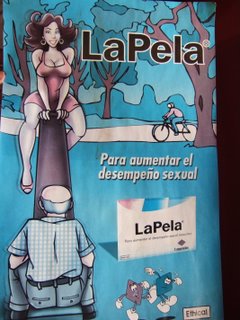

Here is an interesting poster that you see all over the place. I am sure I don't need to explain what this little pill supposedly does. The ubiquity of it is what surprises me, and they sponsor one of the major baseball teams - all those muscly sportsmen with the name of a "male help" pill on their backs.

I am a bit confused over this in a number of ways. Firstly the pill is called "La Pela", and my understanding of the word pela is that it is a slang term for a beating - "I am going to give you a 'pela'" means I am going to thump you. Quite why this is has become a name for a small blue pill is beyond me, though I am sure some feminist discourse analyst could spend many a happy year analysing it.

The link with baseball is also amuses me. There is a rival brand that makes a great deal about how it is endorsed by none other than David "Big Pappi" Ortiz, a major league batsman. Unfortunately, the nickname is not my invention, but on the poster is actually in a larger font than his first or last name. Their publicity has an interesting picture of "Big Pappi"; a huge, grinning, muscly baseballer gripping a baseball bat in a way that clearly shows he is compensating for something. I don't think the concept of male compensation is present in Dominican culture if all the blue pill manufacturers endorse big muscly sportsmen who swing bats. Either that or they have highly developed sense of irony, which I doubt.

Apparently these endorsements are worthwhile, as these pills are incrediably popular. You have young men popping these pills like crazy (surely young men are the people in least need of such artificial stimulants, or maybe I should ask their girlfriends. Though this sort of person probably doesn't have one). It has become a bit of a health risk as it is tampering with blood pressure.

The most surprising bit is that people here will openly talk about how they use them. The DR is an incrediably macho society, and no bloke ever wants to show their weakness here, least of all in the trouser department, yet that is not how it seen here. Rather it is seen as a point of pride that you have so many girlfriends that you need help in keeping them happy. Though I don't see why you couldn't just try helping them go shoe shopping......

Anyway, I think the DR is a long way from metrosexuality. I'll put my plans for a male moisturiser import business on hold.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

For example, meeting Dominican civil servants (who are never particularly civil) are people who work very much on la hora Dominicana (Dominican time). I arranged a meeting with someone at the environment ministry, scheduled it for 10 AM. I arrived at 9:55, all prepared and ready, only for the interviewee to turn up at 11:45, without so much as an apology for being late. I soon became used to Dominican time, and incorporated it into my working day. It is perfectly reasonable here to schedule a meeting a full hour before when you want it, knowing that people will generally turn up around an hour late. Most Dominicans appear to live in a time zone about 1 hour behind GMT (Gringo Mean Time). I have a suspicion that the same social trend observed in the lecture I went to applies here - that the later you turn up, and the more disdain that you give to people who expect you to turn up on time or at least apologise for being late, the greater the sense of superiority and importance that you exude. Perhaps a bunch of anthropologists would get excited by the social power things, and would start talking about Bordieau and such like, but anthropologists are a funny breed, and have a unpleasant tendancy to do things like that.

The problem with this is that I have a lot of meetings with foreigners and with Dominicans working at foriegn NGOs and aid agencies. In the DR, if you want someone to turn up within about half an hour of the scheduled time, you say a la hora Americana - American time. My own practice when meeting Dominicans who work for foreign organisations is to think that they have become half-gringoed, and so I expect them to turn up 40 minutes late. With foreigners who live here, I make a calculation on how long they have lived here, and how aplatanado they have become. For someone new to the country, I expect them on time, but for someone who has lived here for ten years, I expect them to be half an hour late.

Yesterday, I suddenly had to think in European time. I had a 10AM meeting with a German aid agency. I made sure I turned up at 9:55, and lo and behold, my German interviewee walked through the meeting room door at 9:59:59. He may have lived here for years, but there is something in the German psyche that prevents them from being aplatanado with regards to time keeping, no matter how long they may have lived here. I wonder how frustrated he must be with Dominican time keeping.

To my dilemna: I have scheduled a meeting for 9AM on sunday morning with an academic. I know that the interviewee is a foreigner, but has lived here for long enough to become semi-aplatanado. She is an academic (a geographer!!!!), and works for the state university here. Therefore my calculation as to what time I should actually turn up at is thus:

9AM sunday morning

-add 30 mins for being a sunday morning

-take away 10 mins for being a foreigner (she is French)

-add 30 mins for being semi-aplatanado

-add 15 mins for being an academic

-add 30 mins for being a state employee

I therefore calculate that I should turn up at 10:35. Sounds perfectly reasonable. I will let you know later how accurate this was, or whether she answered the door in her dressing gown.

I think I should create a website that does calculations like this, to work out the exact delay between the time-keeping of different Dominicans and Gringo Mean Time.

Friday, December 01, 2006

What 'aplatanado' means

Looking at the license documents and ownership papers, there are few interesting sub-clauses, here reproduced;

- All journeys that are longer than 20 yards must be taken on a motorcycle. If you own a motorcycle, it is undignified to use your feet for anything other than the gear shift and the brake.

- Your horn must be used on the following occasions; approaching a junction, overtaking, undertaking, when there are children/chickens/any other detritus in the road, when passing a vaguely attractive female, when people are trying to get to sleep, all other times. The horn is more important for your safety and wellbeing than your brakes - it is used more and should be serviced more regularly.

-In the interests of public wellbeing, your engine should be tuned so that it is as loud and high pitched as possible. Please visit a mechanic if it is not harming the navigation abilities of all bats in a 20 mile radius.

-If possible, avoid making any journeys alone that can't be made with your wife, three children, a propane tank, two chickens, a live goat and a sack of rice on the back.

-When not making journeys, you and your motorcycle should be parked outside the colmado, revving your engine and showing the world you are a man with a bike.

I notice that I have offended people (Chirimoya and friends) with my comments about Dominican cooking and cuisine. I stand by my comments, and invite them to prove me wrong, by having me round and cooking me a great dinner. Over to you.